Ornithologist Jameson Chace and his students at Salve Regina University walk the Cliff Walk in Newport every other week from December through March to count the ducks they see in the water. They often count large numbers of scoters, eiders, scaup, buffleheads, goldeneyes and other species, but their numbers vary significantly from year to year.

The same phenomenon occurs throughout Narragansett Bay – large numbers of ducks are observed some years and many fewer during other years. And no one seems to know why.

“Because birds move around a lot, we can’t really say much about trends, but there have been

years when I’ve seen rafts of scoters in massive numbers and many years when there’s not,” said Chace,

|

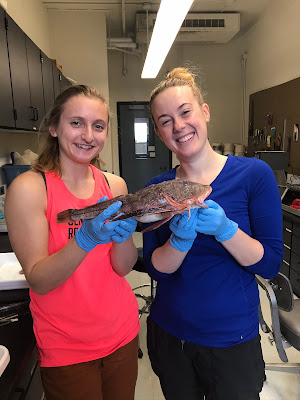

| Common eider |

a professor of biology at Salve Regina and the president of the

Wilson Ornithological Society. “There seems to have been a lot more birds in wintertime when I was a kid than there are now, and that’s true for some particular species – like scoters and goldeneyes – though some others are consistent.”

Rick McKinney agrees. An ecologist for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, he has organized an annual survey of waterfowl in Narragansett Bay every year since 2005. Six teams of volunteers visit more than 60 sites around the bay on a designated day in January to count waterfowl, and their results are similar to what Chace has found: duck numbers vary widely.

McKinney and his team counted nearly 22,000 ducks of 16 species in 2005 but just 15,000 the following year. In 2018 duck numbers skyrocketed to 31,000 but declined to 17,000 in 2020.

“Things fluctuate a lot, but in the grand scheme of things, I don’t think we’ve seen any tremendous declines or increases,” he said. “We tend to get a total number of around 20,000 individual ducks every year, and it’s pretty consistent. But it definitely changes from year to year.”

Common eiders are a good example. On his surveys, numbers of eiders – known for their fluffy down feathers used in jackets and comforters – ranged from 2,400 in 2005 to 130 in 2016 and 5,700 in 2018.

“Their numbers are all over the place,” McKinney said. “What causes it? I have no idea. It could have something to do with food availability or their general distribution on the East Coast. Maybe some years they don’t migrate down this far because they’ve got enough food in Maine. But that’s total speculation.”

McKinney noted that eiders eat mussels, and many of the mussel beds in Narragansett Bay were “fished out” in the 1990s and early 2000s, which may have led many of the birds to seek food elsewhere. But why would there have been so many in 2018?

He thinks the weather probably plays a role. That was the year when McKinney counted 31,000 ducks in the bay, and it was a very cold winter.

“The bay was frozen down to Prudence Island that year and we didn’t think we’d see many ducks because the northern part of the bay was out of the picture,” he said. “But I think all the birds got pushed down from the north because there was little area of open water up there, so Narragansett Bay was teeming with waterfowl. I went to one spot where we usually count seven ducks and there were thousands.

“If there’s a winter where there’s not much freeze-up of waterways to the north – like the St. Lawrence or the coast of Maine – then ducks may stop there on their southern flight and not make it down here,” he added. “Other years when it freezes up there, we get more ducks here. That could have something to do with it.”

That could also mean that the warming trend due to the climate crisis could result in fewer ducks wintering in Rhode Island in the future, even if overall populations remain unchanged.

One species that appears to have declined significantly since the beginning of the surveys is greater scaup, which often were initially seen in large groups totaling 7,000 to 10,000 individuals, mostly in the upper bay. McKinney said scaup numbers nose-dived in 2011, and now just 3,000 to 5,000 are consistently seen each year.

“That’s another big mystery,” he said.

Jenny Kilburn, a wildlife biologist at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, has also noted a decline in scaup numbers in the aerial surveys she conducts every winter. Her survey is conducted, in part, to set bag limits for duck and goose hunters, and the decline in scaup throughout the region has resulted in a reduction in the number of scaup that can be hunted this year.

The bag limit for mallards was also reduced this year.

“We’re concerned about mallards because their populations have been declining,” Kilburn said. “In our area, we get eastern Canadian mallards migrating through and our own Northeast population of mallards, and the Northeast population has been declining. There is ongoing research looking into the genetics of the birds to try to figure out why.”

According to Kilburn, Rhode Island is a popular spot for duck hunters, especially those targeting sea ducks like scoters and eiders. She frequently gets calls from hunters from around the country who are interested in coming to the Ocean State to hunt sea ducks. Yet she doesn’t believe hunting is having an effect on duck numbers.

“Hunting is one thing we can change right away if we see a decline,” she said. “We’re looking now at addressing the length of the sea duck hunting season and bag limits to lessen its impact.”

Chace wonders whether the arrival of the invasive Asian shore crab has anything to do with changes in duck populations, since many ducks feed on crabs.

“Asian shore crabs have pushed out our larger crabs, and because they’re much smaller, the ducks have to dive down more often to get the same amount of food,” Chace said. “Maybe they’re wasting a lot of energy that way. That’s got to be a game changer for these sea ducks.

“We’re also seeing changes to our fisheries, and I’m not sure what that’s going to mean for our ducks,” he added. “With black sea bass moving into the area – they’re voracious predators on many small fish – that might be having an impact on food availability for some ducks, like mergansers, that eat fish. But we don’t know.”

Kilburn worries that any duck species that relies on the marine environment for food is at risk from the changing climate.

“Their food resources are changing or declining, so we’re seeing shifts in where the birds go. We’re finding them in different places,” she said.

And yet while the number of ducks counted in local surveys continues to fluctuate from year to year and the birds aren’t always in the places they used to be found, Kilburn is optimistic about the outlook for local waterfowl.

“These are migratory species that are managed across the states and parts of Canada, and there’s a lot of great research that goes into their management,” she said. “Between hunters and conservation groups and state and federal agencies, there’s a lot of support for our waterfowl. So that bodes well for their future.”

This article

first appeared on EcoRI.org on December 7, 2020.